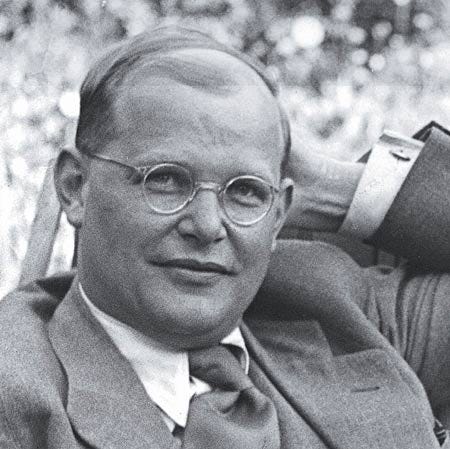

Theologian, Spy and Pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer was martyred by the Third Reich in April of 1945. Along the way, he buried some of his most treasured writings in his house and garden. These were excavated after his death, revealing the work we now know as “Ethics”.

Much of Bonhoeffer’s Ethics is a lament. It’s a lament about watching Dietrich’s Christian friends, pastors and even mentors kowtow to Hitler’s regime, then suddenly - and seemingly magically - finding “scriptural” justifications for doing so.

One of Bonhoeffer’s telling reflections is in his chapter entitled “The Successful Man” - no doubt a barely coded reference to Hitler - and how easily the “Successful Man” can work us up into such a frenzy that we can no longer see what’s right and what’s wrong:

When a successful figure becomes especially prominent and conspicuous, the majority give way to the idolization of success. They become blind to right and wrong, truth and untruth, fair play and foul play. They have eyes only for the deed, for the successful result. The moral and intellectual critical faculty is blunted. It is dazzled by the brilliance of the successful man and by the longing in some way to share in his success. It is not even seen that success is healing the wounds of guilt, for the guilt itself is no longer recognized. Success is simply identified with good. This attitude is genuine and pardonable only in a state of intoxication. When sobriety returns it can be achieved only at the price of a deep inner untruthfulness and conscious self-deception. This brings with it an inward rottenness from which there is scarcely a possibility of recovery. (Bonhoeffer, Dietrich. Ethics pp. 77-78.)

Bonhoeffer has a penetrating psychological insight, here: our desire to share in the power and success of the “Successful Man” blinds us (willingly) to what’s right and wrong. Our desire for success warps our thinking, and justifies anything the Successful Man says, or does, in order to allow us to share in his or her success, since that is our deepest desire.

And yet, Bonhoeffer notes, this entire way of thinking is built on a lack of belief in the gospel:

The proposition that success is identical with good is followed by another which aims to establish the conditions for the continuance of success. This is the proposition that only good is successful…And yet this optimistic thesis is in the end misleading. Either the historical facts have to be falsified in order to prove that evil has not been successful, which very soon brings one back to the converse proposition that success is identical with goodness, or else one’s optimism breaks down in the face of the facts and one ends by finding fault with all historical successes. (78)

This deep drive for success, Bonhoeffer is saying, is built on the idea that goodness will be justified in this life, and evil cannot succeed. This naive - and anti-Christian (Book of Job, anyone? The Cross, anyone?) - view of the world leads us, naturally, to distort all of history. We must erase from our minds the evils done that gave power to the powerful in the first place. But the more one tries to do this, the more one fails.

And that is how radical conservatism leads to radical progressivism: once we become disillusioned with the way power is acquired in this life (through evil), we begin to “find fault with all historical successes”.

And yet this progressivism, Bonhoeffer argues, is an equal and opposite evil:

The arraigners of history never cease to complain that all success comes of wickedness. If one is engaged in fruitless and pharisaical criticism of what is past, one can oneself never find one’s way to the present, to action and to success, and precisely in this one sees yet another proof of the wickedness of the successful man. (78)

In other words, by complaining that all power is ill-begotten, the progressives preclude themselves from ever taking action and having success, and so destine themselves to an embittered, “fruitless and pharisaical” existence.

The irony of both of these perspectives, says Bonhoeffer, is that they equally idolize success, making it the judge and justifier of everyone:

Even in this [progressivism] one quite involuntarily makes success the measure of all things. And if success is the measure of all things, it makes no essential difference whether it is so in a positive or in a negative sense. 78

What is to be done?

In a stunning proclamation of the gospel, Bonhoeffer notes that Jesus’ crucifixion puts to shame both of these perspectives:

The figure of the Crucified invalidates all thought which takes success for its standard. Such thought is a denial of eternal justice. Neither the triumph of the successful nor the bitter hatred which the successful arouse in the hearts of the unsuccessful can ultimately overcome the world. Jesus is certainly no apologist for the successful men in history, but neither does He head the insurrection of shipwrecked existences against their successful rivals. He is not concerned with success or failure but with the willing acceptance of God’s judgement. Only in this judgement is there reconciliation with God and among men. Christ confronts all thinking in terms of success and failure with the man who is under God’s sentence, no matter whether he be successful or unsuccessful. (78-79)

And what is the sentence of God’s judgment?

For those in Christ, it is a “sentence of mercy", through the cross and resurrection:

It is a sentence of mercy that God pronounces on mankind in Christ. In the cross of Christ God confronts the successful man with the sanctification of pain, sorrow, humility, failure, poverty, loneliness and despair…God’s acceptance of the cross is His judgement upon the successful man. But the unsuccessful man must recognize that what enables him to stand before God is not his lack of success as such, not his position as a pariah, but solely the willing acceptance of the sentence passed on him by the divine love. (79)

A parable, perhaps, for our feverish times.

That's really good. A much need reminder to a culture that worships success at all costs.

Bonhoeffer's writing is a strong indictment against my thoughts about my own success. In my mind my vocation should be such and such, and my income level ought to be such and such, and I want to possess those things which confirm a certain vocation and income. I have not attained any of those milestones. I am confident that it is God's reminder that I had been pursuing those milestones for the wrong reasons. St. Thomas Aquinas and Luke 10:27 remind me that the telos of man is to know God, to love Him and to make him known a task which I have been very successful at avoiding and a pursuit which ought to become a focus of my own life.