Last year I was in a little parent pow-wow at my son’s school, and the Head of School was giving us an address basically about how to stay sane when our kids’ hormones are going crazy, the kind of inspirational Chicken-Soup-For-The-Soul injection we need straight in the veins each Fall. The gist of the message, which did not make me comfortable whatsoever, is that we need to be more emotionally mature than our teenagers.

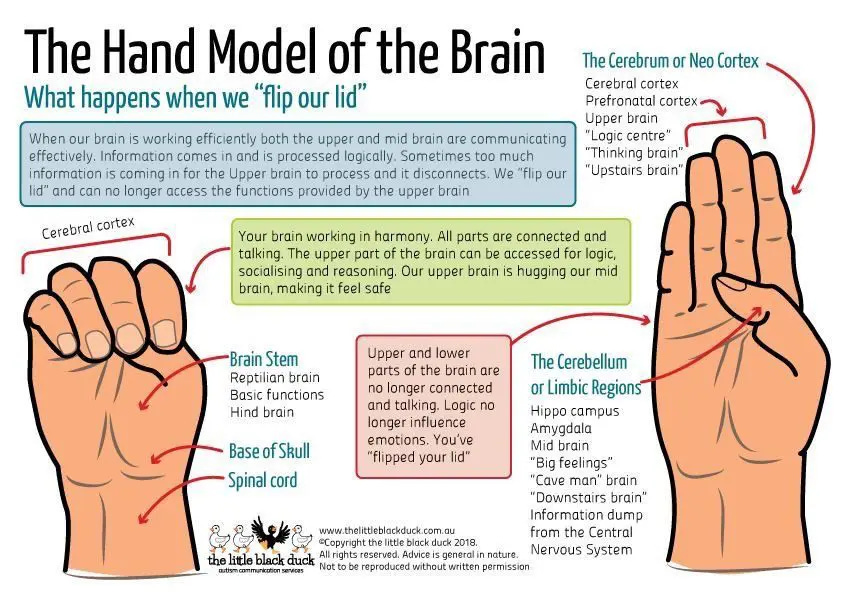

“Your teenagers’ rational brain and emotional brain aren’t quite knitted together yet,” she said. “So when they feel big things, their emotions take over, and they literally can’t think rationally.” She gave a little illustration of fingers being closed around a thumb - the thumb being the rational part of the brain, I guess, and the fingers being emotional - and said that when teenagers have a rush of hormones or dopamine or adrenaline their brain “flips the lid” (and she opened up her hand to show how they disconnect) and they can’t think. They can only feel.

She said for girls, that stuff gets sorted out around the normal adult ages of 18-20, but for boys it’s more like age 25, which is somewhat depressing to me considering I was relating way too hard to this “flipping of the lid” scenario being described and thought it could possibly be more like 52 or something.

“So here’s what you need to do,” she explained. “You need to keep your rational and emotional brain connected, even when your teenager is flipping their lid. I know it’s hard. But think of it this way: you need to be a thermostat, not a thermometer.” I nodded as if to say, “Ah yes, I remember exactly what those devices are and precisely how they connect to your main point,” even though it took me about five minutes to remember:

1. A thermometer reflects the temperature of the room. It’s a mirror of the environment around it, showing what’s there.

2. A thermostat determines the temperature of the room. If the room is too hot, the thermostat cools things down. If it’s too cold, the thermostat heats things up.

This all reminded me a of a conversation I had with my friend Robbie the Philosophy Guy who was talking about his relationship with his son, and how they were both Irish hot-heads and could just go ON in their arguments.

“And we could,” he said. “We could both go on and on, arguing for our points. So here’s what I do now. I just say, ‘Let’s get off the rollercoaster. It’s not going anywhere.”

In other words, if you’re being a thermometer…change directions.

Be a thermostat.

Or, here’s the way I heard it: “You’ve got to be at least 10% more emotionally mature than your kids.” Which really, is pretty hard to do.

This is no parenting blog and I would never make one of those, because I think only brand spanking new parents (also the non-spanking parents) write advice columns for other parents, and I need more sleep anyway before I can even attempt that.

But I did really resonate with what my son’s Head of School was saying about relationships, and about me, and about the church and politics and society in general. Oh wait, did you not catch that part about politics and society? Sorry, let me clarify:

Christians need to be thermostats for society. Not thermometers.

Here’s why: I’m convinced at least one third of our apologetic to the western world is our tone of voice. It doesn’t just matter what we say (that’s important) or what we do (that’s important), but how we say what we say. That’s the great irony of living in the world, isn’t it? We think we’ll be heard when we shout louder, pound the table or perform theatrics. But if you just mute the sound on that picture and think about it from the point of view of someone who disagrees with you, here’s what it looks like:

You’re crazy.

You’re angry.

You’re insecure.

So the question becomes: do you really want to influence culture? Do you really want to turn the tides on secularism? Or are you more interested in having your moment? Is your political and social engagement just a christened way to flip the bird at your perceived threats?

This is a serious question, a really very serious question. And I want you to you wrestle with it, because this kind of moral grandstanding only reflects the same “spirit of the age” - the social media age especially - that the secular culture offers. Here’s what philosophy professors Justin Tosi (Texas Tech) and Brandon Warmke (Bowling Green) say about this, calling it the “rise of moral grandstanding”:

“[W]e often raise issues of justice and equity not to advance meaningful social causes but to generate positive attention for ourselves by denigrating others. Sometimes this involves piling on—joining a Greek chorus of reproachful replies without contributing anything new—or exaggerating one’s moral outrage for dramatic value. In doing so, we dilute the impact of critical ethical issues and foreclose the possibility of productive public discourse. The goal is not to understand but to win.”

Here’s your thermometer: Secular culture is a place of moral grandstanding, which is a move frankly uninterested in doing anything other than loudly patting itself on the back. And while yelling back might feel natural, what that’s actually doing is playing into the secular game and its secularized assumptions.

How can we be people who actually move the needle, rather than reflecting the room around us? Here’s the answer: we need to stop being thermometers.

Christians need to become cultural thermostats.

The Church

Everything I just said is very pragmatic, and I get that. I’m okay with pragmatism, really, considering pretty sound minds have said that’s actually one of the hallmarks of Evangelicals anyway. I own it.

And, I understand the alarmism. Having grown up reading the teenage version of the Left Behind series (the adult version had too many sexual liaisons on airplanes I think), I’m pretty familiar with the kinds of horrifying narratives that make us feel like the world is on a precipice, and we need a great strongman, prince or rescuer to keep us from said cliff. For the past century or so, evangelicals have been living with this kind of vision:

The world is in decline.

Things will continue to grow worse.

Finally, when Jesus can’t take it anymore, he’ll take us out of here…

And burn the whole thing to the ground.

Not much for poetry, but there it is. And here is the thing: if you’re living with that kind of vision of the future, sure. Go ahead and set the alarm bells, site fire to Gondor’s beacons, go bellow into the woods about the Rich men north of Richmond and do just about whatever you can to persevere a scrap of sanity in this God-forsaken world. It all makes sense.

But what if that wasn’t the narrative?

Three things I want to say about this: something theological, something historical, and something data driven.

First the theological thing. I want us to think about some of the images Jesus uses to talk about the kingdom of God. I’m not going to try and convince you to be amillenial, premillenial or postmillenial or give you can kind of specific scheme about Jesus’ second coming. But I’m also unpersuaded by the idea that eschatology - the study of the last things - makes no meaningful difference in our Christian life. As my Lutheran pastor used to say, “We don’t care about your view of the end times, here. We’re panmillenial: it’ll all pan out in the end.”

Ha ha. But I think it’s overstated, because no matter our interpretation of the Book of Revelation, we do need to agree on some basics about what Jesus said about the coming kingdom, because it makes all the difference in the world in how we engage our lives now.

Let’s start with Matthew 13, Jesus’ explicit treatment of the future, framing what his disciples should expect:

Matthew 13:31 The kingdom of heaven is like a mustard seed, which a man took and planted in his field. Though it is the smallest of all seeds, yet when it grows, it is the largest of garden plants and becomes a tree, so that the birds come and perch in its branches.

What does this parable say to us about the kingdom of God? It says pretty straightforwardly that Jesus’ kingdom will have small beginnings, but that it will grow into the largest movement in the world, so much so that “the birds” - the non-Jewish nations - will all benefit from it. The coming of Jesus’ kingdom, in this telling, isn’t a bombshell moment from the heavens when Jesus wipes everything out, but a slow, gradual and nearly imperceptible process. It starts in Jesus’ day, and slowly works its way out, over time.

In other words: the kingdom of Jesus is not shrinking, or “losing” or declining. It’s growing. That’s eschatology 101.

Here’s his next parable:

Matthew 13:33 “The kingdom of heaven is like yeast that a woman took and mixed into about sixty pounds of flour until it worked all through the dough.”

Jesus describes his current work - here and now - as “working the dough” of the yeast he planted 2,000 years ago, until there will be a day when “all the dough is worked through.” Again: slow. Gradual. Kneading. Complex. We’re describing a consistently hopeful vision of the world, here.

Why, then, does Jesus often describe so much hostility toward disciples? Why does he say we ought to expect persecution and hatred and vengeance? Well, let’s think about it. When do people become hostile? Well sometimes, sure, it’s because they have power and they can just do what they want, and they’re bullies. But people most often become violent and hostile when they feel under threat. Which interpretation does Jesus encourage? In Matthew 24, Jesus’ most explicit chapter about persecution, famine, false prophets and all the dreary stuff we should expect in this world, he inserts this beautiful little gem of an image:

Matthew 24:8: “All these will be the beginning of birth pains.”

Do you hear how subversive this is? Jesus is saying: “All this tension, these false prophets, this persecution, is like the tension a woman feels when something healthy and vibrant is growing in her womb.”

In other words: the hostility we experience in this world isn’t evidence of Christianity’s decline.

It’s evidence of the kingdom’s health, vigor and growth.

Demons only scream when they’re exorcised. Otherwise they’re fairly complacent, which is why I suspect we see a huge uptick in talk about demonic activity when Jesus walks the earth. They’re facing their greatest single threat, so they thrash out.

Satan, Demons and the Political Order

“But isn’t Satan in charge? Doesn’t the Bible say that explicitly?”

Well, here’s Jesus’ take on that:

Luke 10:18: “I saw Satan fall like lightning from heaven.”

It’s not a coincidence, either. This is explicitly what he came to do:

John 12:31 - “Now is the time for judgment on this world; now the prince of this world will be driven out.”

Satan, according to Jesus, has been dethroned through his earthly ministry. The kingdom of the world belongs to Christ, and he’s claimed it through his life, death and resurrection. The ascension is significant here: it’s the sign that Christ has taken up the throne of the world, and that things, from here on out, are set in flint: the rising, growth and spread of the kingdom is inevitable.

But what about that tricky passage about Satan being a prince? Or passages that seem to indicate Satan’s exertion of power over the whole world?

Language is key, here. So yes, Ephesians does say:

Ephesians 2:1-2: As for you, you were dead in your transgressions and sins, in which you used to live when you followed the ways of this world and of the ruler of the kingdom of the air, the spirit who is now at work in those who are disobedient.

But a little context is in order.

First, the grand point of Ephesians is that Jesus is King over every authority: physical, spiritual, celestial and otherwise. That’s what he just stated, in Ephesians 1:21-23, which is about God’s “incomparably great power”:

“That power is the same as the mighty strength he exerted when he raised Christ from the dead and seated him at his right hand in the heavenly realms, far above all rule and authority, power and dominion, and every name that is invoked, not only in the present age but also in the one to come. And God placed all things under his feet and appointed him to be head over everything for the church, which is his body, the fullness of him who fills everything in every way.”

Jesus is King over - wait for it - every heavenly and earthly authority “not only in the present age but also in the one to come.” The kingship of Jesus is not merely a future reality, but a present reality, because of the cross and resurrection. Or, to put it more explicitly, as Paul writes to the Colossians:

Colossians 2:15: [H]aving disarmed the powers and authorities, he made a public spectacle of them, triumphing over them by the cross.”

Satan has already been dethroned.

The reign of Christ is active, current, and its climax is inevitable.

Prince of the Air

Now when we turn the page to Ephesians 2:2, we should hear the term “the ruler of the kingdom of the air” in that broader Jesus-as the-authority-relativizing King kind of context.

And might I suggest that Paul’s term for Satan’s “rule” here is…rather diminishing?

Satan, notably, is no king (different greek word, basileus). He’s merely a “ruler”, or a little prince. And though there’s debate about what the term “the air” means, all scholars agree this is referring to some kind of sub-realm of the entire creation. In other words, what we all must believe, no matter our eschatology, is that Satan’s role has been diminished on this earth because of the resurrection and ascension of Jesus.

But I, personally, would go even further.

Think of this: nowhere does Paul use the word “air” (aeros) to refer to the spiritual realm. Rather, he uses it to refer to empty, meaningless space. For instance, in 1 Corinthians 14:9, Paul accuses the Corinthian church of speaking tongues “into the air”, meaning: their words are going not into some evil spiritual realm, but…nowhere. Empty space. A place of no significance. And again, in 1 Corinthians 9:6, Paul says he’s not fighting “as if beating the air”: in other words, his fight isn’t into an empty void, or a meaningless space. And given these majority uses of the same word, isn’t it at least possible that Paul is actually saying this about Satan (to put it in the immortal words of Bugs Bunny in Space Jam):

“He’s a rather diminutive fella, ain’t he?”

What if Paul wasn’t honoring Satan’s role in the world, but mocking him? What if he’s saying, “Satan’s the lord of the meaningless, empty space. The things he has charge over are passing away. And so is he.”

That’s my take, anyway. But even if that’s not true, again, all scholars agree that Paul, here, isn’t wanting us to walk away awed by Satan’s reign, but by Christ’s current and future reign over Satan. Any other interpretation would betray the entire thrust of Ephesians.

But there’s one more thing that trips us up. Paul refers to Satan as the ruler of “this world”, and that sounds pretty big. If he’s mocking Satan’s rule and diminishing it, why does he say Satan is ruler of the whole world?

It’s because the term kosmos, for Paul, doesn’t refer to the entirety of heaven and earth. For that, Paul uses the more comprehensive Hebrew phrase, “heaven and earth” (as he did in Ephesians 1). Rather, the “world” merely refers to the patterns of opposition to God’s kingdom. So when John, for instance says, “The world and its desires pass away, but whoever does the will of God lives forever”, he’s not saying heaven and earth will be destroyed (they are, as per his vision in Revelation 21:1, to be renewed and rejoined). Rather, he’s saying the evil patterns of this world - both individually and corporately (thus, “its desires”) - will pass away. And those evil patterns are what Satan has power over…but they are “air”. They’re fading away.

A new kingdom has already arrived, and is growing stronger: the Kingdom of God.

The gospel of the kingdom gives us reason for hope. It gives us reason to move from alarmism to confidence. “But look around us!” you may say. I will do that…next week. I think both history and statistics very clearly bear this kingdom vision out, despite the doom narratives we’re often presented in the evangelical world. But I’ve already covered a lot of terrain (more than I thought), and I’ll need to spell that all out next week, then get into some practical applications of the thermostat strategy.

Hey All,

For those of you who have become paid subscribers, I’m so grateful for your support and words of encouragement. It means the world to me.

I’ll be offering 20% off for another two weeks.

When you become a paid subscriber, you not only support my work, you’ll also get access to my weekly cultural roundup, below (it’ll be free for two more weeks).

Gospel in Culture

Interestingly, this week there are two great articles about the religious impulse behind violence in our culture. The first explores why little girls have the impulse to be violent toward their Barbies. The second explores why so many pop stars are getting pummeled by flying objects. Both of them point to religious impulses in all of us: the need for someone to be the beauty we can’t be, and to take the evil we can’t fix. Sound familiar?

In the last throes of Summer, I’ve been enjoying a couple of feel good summer vibe type things, the first of which is “This is Clarence Carter”, a great and under-appreciated album. Carter’s gravelly voice and belting, bluesy melodies are perfect for savoring the last few sunny days (for us Hoosiers, anyway) of the season.

The second summerish thing I really, deeply enjoyed was the 1986 film “Stand by Me”, a story about boyhood, friendship, and our collective longing for a clear identity and mission. A great line in here: “We knew exactly who we were and exactly where we were going. It was grand.” It was a fantastic film, from beginning to end. As I explained it to my friend, “It’s The Sandlot, except instead of a baseball it’s a dead body.” Watch it and tell me I’m wrong. I loved this movie.

Andrew Abernathy’s book “The Book of Isaiah and God’s Kingdom” was a fantastic exploration of Messianic expectations, and how Jesus both subverted and fulfilled them. Abernathy is careful to maintain the integrity of Isaiah’s original vision, but he’s also willing to show how Jesus fulfills this vision without betraying it. I loved the way this study brought out the subtle nuances of Jesus’ gospel message with such academic rigor and grace. I’m basing a whole chapter of my new book on Abernathy’s work. One of my favorites from the “New Studies in Biblical Theology” series, which is saying a lot!

An excerpt I’m pondering, from Keller’s “Jesus the King”:

In an interview Andrew Walls, a distinguished historian of world Christianity, noted that wherever the other great world religions began, that is still their center today. Islam started in Arabia, at Mecca, and the Middle East is still the center of Islam today. Buddhism started in the Far East, and that’s still the center of Buddhism. So too with Hinduism—it began in India and it is still predominantly an Indian religion. Christianity is the exception; Christianity’s center is always moving, always on a pilgrimage…

…In the year 1900, Africa was only 1 percent Christian. Now Christians make up nearly half the African population. In the next fifty to seventy years, the center of Christianity is predicted to complete this shift away from European countries and from the United States. It will migrate, as it always migrates.

In the interview with Andrew Walls, he was asked, “Why does this happen? If the centers of other religions remain constant, why does the center of Christianity constantly change?”

Walls replied: “One must conclude, I think, that there is a certain vulnerability, a fragility, at the heart of Christianity. You might say that this is the vulnerability of the cross.” The heart of the gospel is the cross, and the cross is all about giving up power, pouring out resources, and serving. Walls hinted that when Christianity is in a place of power and wealth for a long period, the radical message of sin and grace and the cross can become muted or even lost. Then Christianity starts to transmute into a nice, safe religion, one that’s for respectable people who try to be good. And eventually it becomes virtually dormant in those places and the center moves somewhere else.

Shalom,

Nicholas McDonald

Loved the content.

( But you’re in need of a “typos” editor. I am sometimes struggling to make out the meaning of the sentence for one wrong word. )

Great starting analogy. I couldn’t help but see the parallels to Autism. Autistic anxiety shuts down the brain. This is why so many people mis-estimate the intellectual capacity of a person with Autism.

If you give a well written, insightful essay to one individual and tell them that it was written by the person they admire the most, they are likely to be effusive with their complements and treat it similar to a word from God.

But if you give that very same essay to another person and tell them that it was written by a person with Autism they are more likely to view it through a different “lens” and say, “No, who wrote this, really.” or they may say something that indicates that they think it is cute or adorable.

Very enlightening definition for “air”.

It seems to give a new flavor to the old phrase “Putting on airs.”

On Satan’s power:

He has as much power as we give him.

We are free agents in practice, even though we were bought with a price. But he, or more accurately his proxies, are always whispering in our ears. And we are more likely to say, “Oh what a clever boy am I for this idea I just had.” Rather than saying, “That’s not right.”

It’s because we’re not immersed in scripture.