These past few weeks I’ve spent a lot of time trying to give a framework for the principles I’ll be laying out through the rest of this series. So I do hope these next few posts will be a bit more zippy. It was occurring to me as I wrote these past few weeks that, in order for the rest of these strategies to make sense, we need to frame the situation correctly, which took quite a lot of legwork. Hopefully it was a decent enough summary of where I’m coming from that, even if you’re not fully on board with the kingdom-of-God-as-a-woman-in-labor thing, the rest of the picture I’m painting will feel at least coherent to you. If you’re anything like me, you’re a pragmatist at heart, so you’re suspending judgment on the way I’m framing the whole big historical/theological situation we’re in until you see how it might play out if we were to frame things that way.

Fair enough. So let’s get to brass tacks. Our first strategy was to “think like a thermometer, not a thermostat”, meaning: we need to maintain a realistic pulse on the secular decline of culture, while simultaneously holding to the truth that the kingdom of God does not require government cooperation. In fact, it often thrives in environments where attempts are made to suppress it. That is not an all-encompassing word, but it is a hope.

One of the reasons, I argued, that we need to hold onto gospel hope for our culture is that our culture requires so much Christian architecture to be the thing that it is. Western culture is far more “christened”, you could say, than pagan Rome. Which means that, in fact, Christians often share similar values and presuppositions to our neighbors who - in their own minds, at least - want nothing to do with formal Christianity. Which leads me to our next strategy: The Columbo strategy.

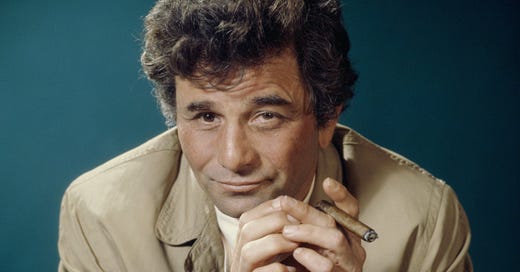

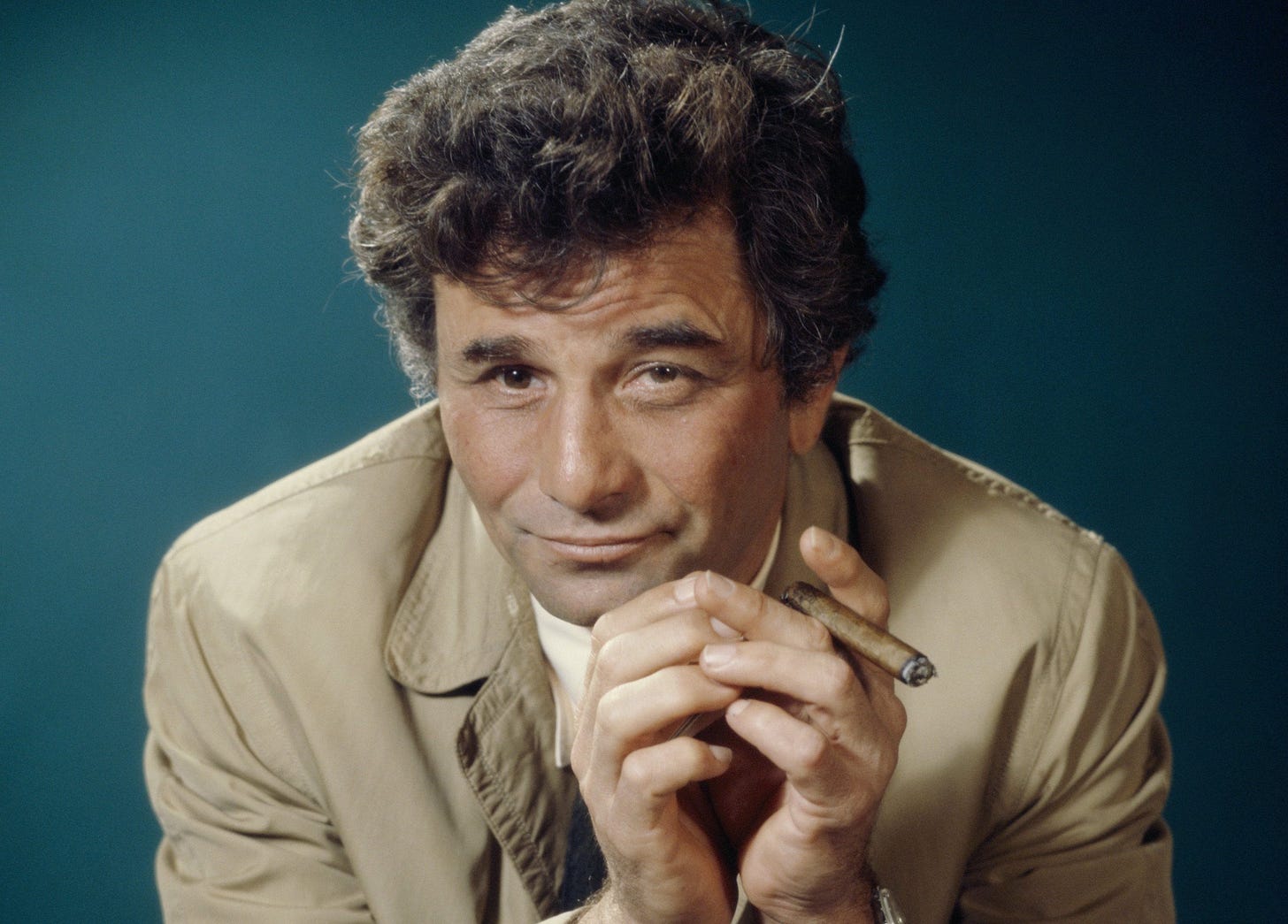

Even if you haven’t seen the show, most of us are likely familiar with Peter Falk’s famously shabby detective, Inspector Columbo (I’ve actually come to learn this show is gaining some traction again with a younger crowd, which tickles me). But if not, the show’s major premise was a bit…insane, at least if I had been sitting in an exec chair assessing it. The premise was this: “What if we show the solution to the murder at the beginning of the show?”

The idea was that, with Peter Falk’s eccentric, Socrates-like detective Columbo as the lead character, the audience didn’t really need to be held in suspense about the murder. Rather - the premise went - they would be held in suspense as to how detective Columbo would solve such seemingly flawless crimes, week to week.

The climax of every episode came - inevitably - with detective Columbo seemingly on the brink of defeat. The crime was too perfect. It was the one he couldn’t solve. But then, just as it seems the killer has every question answered and every detail expected, Columbo begins to slump away, does a turn about, and…

“You know, just one more thing one small little thing it’s no big deal I’m sure but I was just wondering…”

And that’s when Columbo names the one detail that doesn’t fit into the narrative the killer’s been spinning, and we know: “He’s got em’ again!”

Our Cultural Narrative

The beauty of the Columbo stories (or at least the fun of them) is the way detective Columbo actually concedes so much of the killer’s narrative. In fact, this is what makes the cases at first seem so unsolvable: the killer’s story is almost all completely true. What’s out of sorts is only one tiny detail…but that detail, as it happens, invites an entirely new interpretation of the (mostly) true story the killer is telling.

It’s actually that very conceding of the killer’s narrative that makes Columbo so effective a detective. If, for instance, Columbo came out with arms swinging - “You did it! I know it was you! I’ve eliminated all the other suspects!” - he couldn’t achieve the effect he creates: he builds trust with the killer. He shows himself to be reasonable, thoughtful and humble. And he genuinely is. But, like Socrates wandering the streets of Greece and asking his innocent little questions about the gods, there’s much more to Columbo than meets the eye: Columbo’s had his own narrative of events from the very beginning. And, almost always, he’s been right all along.

Why all this Columbo mumbo jumbo?

It’s because I think the evangelical tactic could use a cue from Peter Falk, here. So often, the evangelical strategy has honed in on the differences between Christians and non-Christians. This is the entire tactic behind the “worldview” approach to Christianity.

1. Let’s make a list of all of the different ways Christians believe differently than non-Christians.

2. In fact, let’s make the list far longer than the historic creeds. because we don’t want Christians to come even close to a non-Christian worldview.

3. In fact, let’s show how in every aspect of life - politics, science, literature, entertainment, etc - Christians must be entirely different from secular culture, because we have a different worldview. We must have a different philosophy and approach to each of these things, which we will call “distinct”. (For a brilliant example of this kind of thinking, see Chris Hatch’s little summary of a conversation between Bono and Franklin Graham)

4. Let’s teach the next generation to see that in every aspect of life, secular culture has got it wrong, and Christian sub-culture has got it right.

In other words: let’s concede nothing. Let’s come out with arms swinging, showing that everything outside of the Christian bubble is faulty, corrupt, and deranged to its core.

There are a couple of major issues with this approach.

First, and most pragmatically, the problem with this approach is that it has a tendency to backfire. That’s certainly what happened with me during my college years. As I began to listen to voices outside of christendom, I was discovering things I had thought couldn’t exist outside of my Christian bubble: true insight from non-Christian philosophers. True beauty from non-Christian artists (and almost always superior beauty to what was produced by so-called “Christian” artists). True love and warmth from friends who were frankly hostile to my own belief system.

I’d expended so much energy combatting these dark forces that when I actually met them, my first instinct was to think: “Everything I’ve ever been taught is wrong.”

I’ve always struggled to find an analogy for this experience, and the only one I have is pretty clunky.

But here it is.

The Christian Worldview movement, for me, was like being taught that Christianity was a four-legged stool. After being exposed to lots of amazing, gifted people outside of this bubble, I felt like one of those legs had been removed, and that made me think the Christian stool itself was no longer something I could rest on. So I backed away from it for a period of time.

It wasn’t until I experienced Christianity in a European context that I realized the “fourth” leg on the stool - American Christian subculture - wasn’t really ever meant to be there in the first place. Christianity had been a three-legged stool the whole time.

I realize that is kind of cheesy and dumb and mostly doesn’t work. But that’s the best I can come up with. And when I describe it that way, I always get a lot of murmurs and nods from folks who had a very similar experience to mine.

“Yes, that’s exactly what happened to me,” they will say, “just without the trip to Europe or the weird furniture analogies.”

So this is the first issue with the combative approach to Christian apologetics. When we condemn everything about secular culture, we’re setting the next generation up to dismantle the barriers we’ve created…because they don’t really need to be there in the first place. And we’ve made it extremely difficult to disentangle our own Christian sub-culture from historic Christian faith.

God’s Grace

The second issue with trying to condemn the secular narrative wholesale is this: it’s a denial of God’s grace.

We could make a long list and draw out a long theological argument as to why we should be looking for God to be at work within what we call “secular” culture.

The first and most straightforward argument comes from Romans 1, when Paul talks about the pagans outside the Jewish fold:

“[W[hat may be known about God is plain to them, because God has made it plain to them. For since the creation of the world God’s invisible qualities—his eternal power and divine nature—have been clearly seen, being understood from what has been made, so that people are without excuse.” -Romans 1:19-20

Paul isn’t of course endorsing pagan philosophy, here, or anything close to it. He’s laying out a philosophical (and moral) critique of the Roman way of life. But he does indicate in Romans 1 that the pagan relationship to truth isn’t as straightforward as the Worldview movement would have us believe.

For one, he says, the truth about God is “plain” to non-Christians. It has been “clearly seen” by the created order, which for Paul isn’t referring merely to the physical world, but to all aspects of creation: the physical world, the philosophical realm, the moral realm…all of these, in Paul’s jewish conception, are part of God’s “creation” (the physical/spiritual duality is more of a Gnostic conception, which Paul would have rejected out of hand).

So what we would expect to find, if Paul is drawing his lines correctly, is that in pagan philosophy, music, art, literature etc. we have, in some ways, glaringly obvious evidence of God’s goodness as well as what he calls “suppressions” of the truth. But even the language of “suppressing” the truth (Romans 1:18 - “who suppress the truth by wickedness”) is a far more complex picture of paganism - or let’s say secularism - than the evangelical movement tends to paint, because it indicates that the relationship of secularists to truth, goodness and beauty isn’t black and white. It’s more like a facebook relationship status: it’s complicated. To “suppress” the reality of God, you could say, is like trying to wrestle a water buoy down beneath the surface. Try as you might, it’s going to bobble up and show itself.

We see the way Paul himself treats pagan philosophy in his famous speech at the Areopagus, where he observes a statue “to an unknown god.”

Paul then stood up in the meeting of the Areopagus and said: “People of Athens! I see that in every way you are very religious. 23For as I walked around and looked carefully at your objects of worship, I even found an altar with this inscription: TO AN UNKNOWN GOD. So you are ignorant of the very thing you worship—and this is what I am going to proclaim to you. Acts 17:22-23

This is an incredibly complex speech. On the one hand, Paul says, “You are very religious”, even going so far as to affirm the fact that in a way, these men of Athens are worshiping God: “You are ignorant of the very thing you worship.” What a statement!

1. You do worship God. You are very religious. AND:

2. You are ignorant of this God you worship.

He then goes on to quote two pagan poets in the speech:

‘For in him we live and move and have our being.’ As some of your own poets have said, ‘We are his offspring.’” Acts 17:28

Paul, here, even goes so far as to use non-Jewish language to describe our relationship with God. To say that “we are this offspring” is clearly pagan language, referring to the “hatching” of humanity from Zeus. Nowhere do we read of Jewish Rabbis using this terminology to refer to our relationship to Yahweh. And yet, Paul hears the way God has already been at work in Greco-Roman culture to draw these people to himself. And so, he begins by naming God’s grace among them. The tenor of the speech is something like this: “Your greatest poets and philosophers, they are onto something. The story they are telling has so many true elements to it. However…”

Paul turns about, winks, and says:

“There’s just one more thing one small little thing it’s no big deal I’m sure but I was just wondering…”

He finds the common thread, tugs on the loose string, then unravels things from beginning to end. Rather than condemning the secular narrative, he subverts it. This is because he sees the way God is already at work in Greco-Roman culture, and he joins in.

It’s only after this that he’s able to reweave the gospel story he’s had in his back pocket all along.

This worldview argument maps perfectly onto my late 90s decision about schooling for my three kids. I asked an administrator why I should send them to Christian school and quickly bought his “Biblical worldview” reasoning. My kids did fine for the most part, and the schools were good, but I’m not sure I would do it for that reason again.

Nancy Pearcey writes books about Christian world view but also affirms where the pagans/secular culture get it right and uses that as a point of connection. Would fit well with your Columbo strategy.